“I mean, I have always been a knife freak,” laughs Quarton. Growing up in Wisconsin, Quarton originally had a woodworking shop and was a furniture and cabinet builder. “I was always working to keep all of the tools sharp,” he says, “I loved all of the sharp things.” In his 20s, he knew the woodworking route wasn’t for him and sold part of his cabinet business to a friend. It was around that time when he saw a book, “Knives and Knifemakers” by Sid Bateman. “I was absolutely fascinated,” Quarton says.

So he took the $3,000 inheritance he had received from his godmother and went out and bought all of the stock to make knives. “At this time nobody was really forging,” says Quarton. “The style was more cutout and I was soaking up every piece of information I could find on the subject.” With no formal programs or the internet to rely on, Quarton read books. “I found a guy in California who wasn’t all that nice, but he was a knowledgeable a knifemaker and I would just call him up and ask him a ton of questions.”

Armed with books and a bit of advice from more experienced knifemakers, Quarton started making his own knives. “And I quickly realized no one was buying them,” Quarton laughs. A bit defeated, he visited his parents in Ketchum. “I remember bringing my knives to this fly shop and they bought four instantly,” says Quarton, “and I thought, welp, I gotta move to this place!” So he packed up his Toyota Land Cruiser station wagon with everything he owned and all his knife supplies and drove out to Idaho to stay with his sister for the summer.

“My first gig in Ketchum was at this little shop on the corner by the stoplight,” says Quarton. “It was a ski tuning shop in the winter and they didn’t use it in the summer so I had this perfect spot on Main Street to set up my own little shop.” After the summer was over, Quarton would drive 36 hours back to Wisconsin. But before long, the drive and the back and forth lost its romance and he decided to move full-time to Ketchum where he was starting to gain a reputation for quality knifemaking.

With the move to Idaho and his skill set growing, Quarton started attending knife shows around the country. “I went to one show put on by the Knifemakers’ Guild in Kansas City and I was absolutely astounded at the work showcased at that event.” He followed that with a trip to a “Hammer In” held in Dubois, Wyoming where he met Bill Moran, a pioneering knifemaker who is best known for reintroducing pattern-welded steel (often called Damascus) back into modern knife making.

Until this point, Quarton was using a cut-out method where the knife blade is a stock removal and then a grinder is used to shape the steel into the desired finished piece. But after meeting Moran and participating in a workshop where he got to experience Moran’s style of knifemaking, Quarton went back to Idaho and set up his first forge.

In the early 1980s, Quarton, keen to continue to learn more about different knifemaking styles, applied for an Idaho Arts Council grant and won. With the money from the grant, he was able to go live with a Japanese swordsmith in Colorado for several months. “It was a wild experience, a full immersion experience,” says Quarton. “He took me through the entire process – from making and cutting down charcoal to building forges to finally forging in the traditional Japanese sword style.” A style that Quarton continues to pursue today.

After his time in Colorado, Quarton’s knifemaking skills were noticed at a national level when he won Best in Show at the 1984 New York City Custom Knife Show. “I was honestly just a kid who flew into New York with a suitcase full of knives,” laughs Quarton. But with a national win under his belt and wealthy clientele back in Idaho who sought him out for collectible knives, Quarton was making a name for himself.

“It was kind of a wild time,” says Quarton. “I had clients who would want really technically difficult designs or requests to use materials like Mastodon tusk or fossil walrus ivory for the knife handles.” He was even commissioned by Sylvester Stallone to make a custom knife.

Then one day, a customer walked into his shop and asked Quarton to make something called a “slick” which used in timber framing and woodworking. “I didn’t really want to make it, but figured it was easy enough,” says Quarton. “We ended up taking it to the Timber Framers Guild Conference and that inadvertently kicked off an entirely new line of business.”

It turns out that Barr Quarton is just as skilled in making hand-forged tools as he is in knifemaking. From that original slick to chisels, draw knives, gouges, and chair-building tools, Barr Specialty Tools has grown to become a much sought-after brand in the woodworking industry.

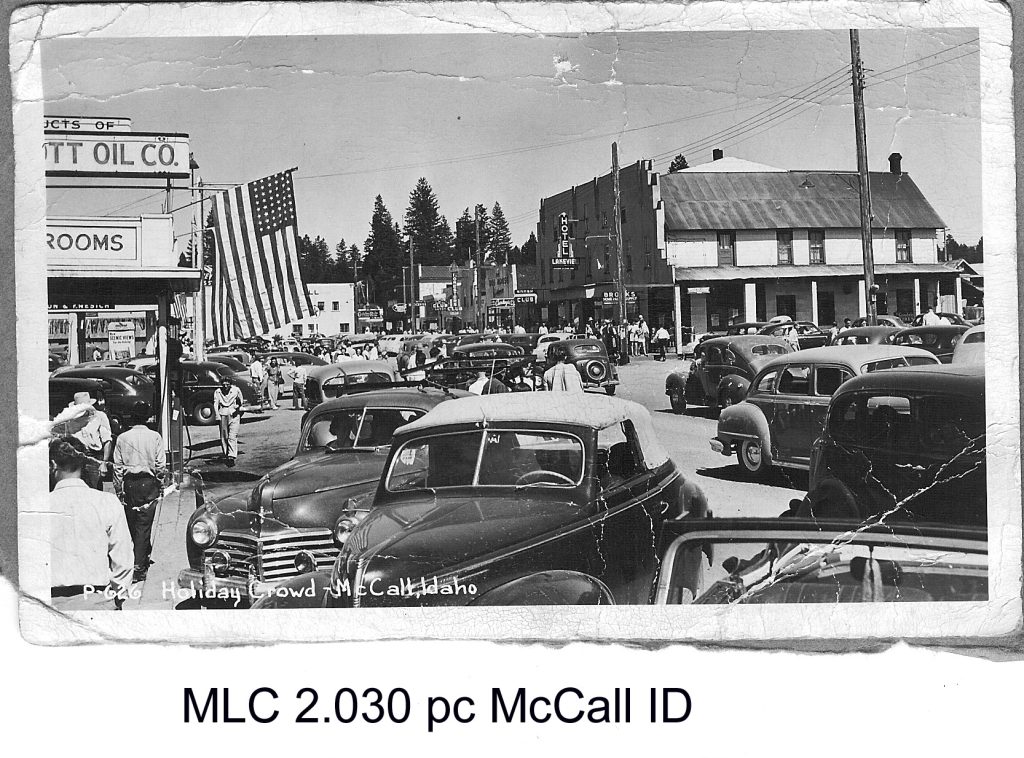

Now, after 30 years of building Barr Specialty Tools in McCall as his primary business, Quarton is passing the torch to his son, Jess, so he can go back to his true passion…knifemaking. “I still love the forging,” says Quarton. “I mean, who wouldn’t?” With Barr Specialty Tools relocating to Boise, Quarton’s shop in McCall is once again his own domain. “I am excited to get back into the Damascus style with a new forge that will give me more heat and open up some new possibilities.”

Just as long as it has function. “Some of the younger knifemakers do beautiful work, but it is all bling,” says Quarton. “For me, a blade has to perform well.” Which is why you’ll find Quarton working on functional blades like his new line of chef knives or a custom hunting knife that will last for generations. And in keeping with his dedication to function, Quarton has also stepped into some custom lighting projects that keep his skills sharp and challenge his creativity. “I am always after something artistic, not something that looks manufactured,” says Quarton.

Which is one of the biggest challenges with forging…the imperfections. “I am honestly not sure if I have ever crafted a truly perfect, unblemished blade,” says Quarton. “Forging is a really crazy mix of heavy duty and delicate tasks,” he says. “There’s a finesse to it. It really is a skill, a craft.”

As Quarton continues to pursue his life-long love of all things sharp, he says his ultimate commission would be three swords: Katana , Wakizashi, and Tanto. “If I can forge one good traditional Japanese sword before I die, that would be the ultimate accomplishment,” says Quarton.

In the meantime, you can find Quarton in his shop, crafting a continuous stream of one-of-a-kind pieces of functional artwork…all with a sharp edge.

Find Barr Quarton’s work on his website at barrcustomknives.com.