Esprit de Corps

The Legend of the McCall Smokejumpers

By McKenzie Kraemer

You may have heard of Sharlie, our friendly lake monster. She resides in the depths of Payette Lake and makes infrequent appearances only a lucky few have been able to witness. She is a bit elusive, and a whole lot mystical. And despite the rarity of seeing her in action, everyone who lives here understands that she is a major thread in the fabric of our local lore.

But she isn’t the only legend in McCall.

Set on Mission Street, just to the west of the McCall airport, there is another elusive, and somewhat mystical being…the McCall Smokejumper Base. Like Sharlie, an occasional glimpse of a smokejumper may catch your eye as they make a few practice jumps in the spring. But you have to be in the right place at the right time. Most of their work is done in the heart of the wilderness, over impassable terrain that many of us will never set foot in. And while we may not always see the work they do, there is no denying the impact the men and women who have earned the title of “McCall Smokejumper” have on our community. Like their lake monster counterpart, they too are an integral part of the history and flavor that is uniquely McCall.

…………………………………………………….

This past April, the McCall Arts and Humanities Council provided a rare opportunity to bring these local legends into the light at their annual Heritage Night. This is a night dedicated to hearing stories and celebrating the people, traditions, and culture that make this community special…and this year, Heritage Night celebrated the McCall Smokejumpers. This stage gave us a behind-the-scenes look at the life of a smokejumper – from training to what it’s really like to jump out of a plane to close calls and amazing feats.

From the history to the training, the call to the jump, the story of the McCall Smokejumpers was brought to the surface, and here, we do our part to share some of that magic.

The History

Smokejumping was originally proposed in 1934 by T.V. Pearson, Regional Forester of the Intermountain Region. His theory was that fresh, self-sufficient fire fighters could parachute into rugged terrain and provide a quick, targeted initial attack on forest fires. The response from the superiors in the Washington DC office were more than a little skeptical, going so far as to say “All parachute members are more or less crazy and just a little unbalanced. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be engaged in such a hazardous undertaking.”

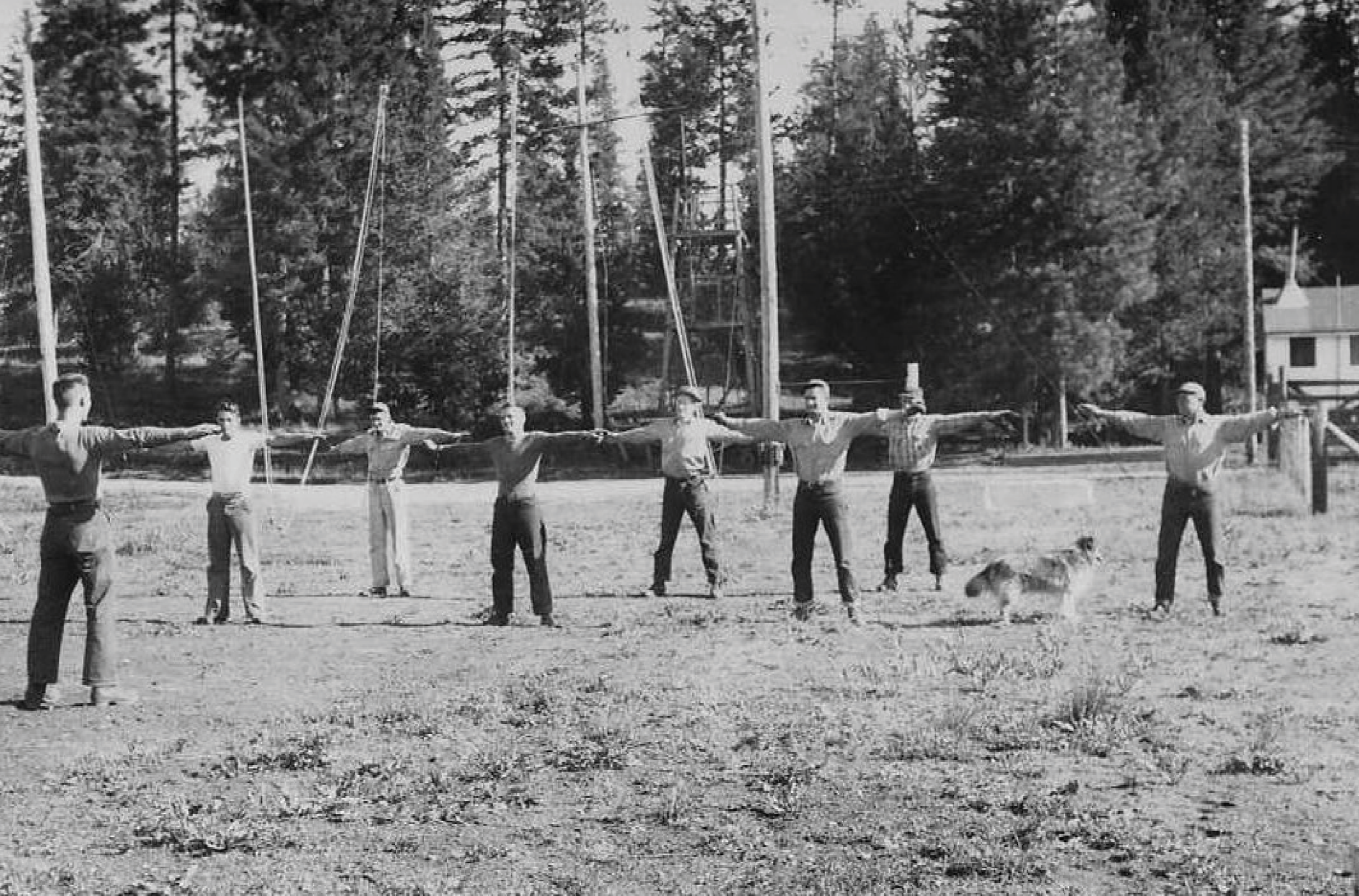

Despite the initial skepticism, the “smokejumper experiment,” as it was referred to at this point in time, persisted. In October 1939, sixteen participants engaged in a trail to test the viability of parachuting. They were divided into three teams: the ground crew, the aircrew, and the parachute crew. Through these trials, each group photographed or filmed activities and outcomes and kept meticulous journals to record observations. Over the course of this experiment, modifications were made to equipment, jump suits, protective gear, and protocols. In the end, the “smokejumper experiment” proved that not only was delivering wildland firefighters by parachute possible, it was vital to fighting remote wildfires.

On July 12, 1940, the first live jump was made by Rufus Robinson and Earl Cooley into the Nez Perce National Forest to fight the “Rock Pillar Fire.” That first jump was the beginning of an elite division of wildland firefighters who continue to play a significant role in fire management efforts throughout the nation (and even abroad) today.

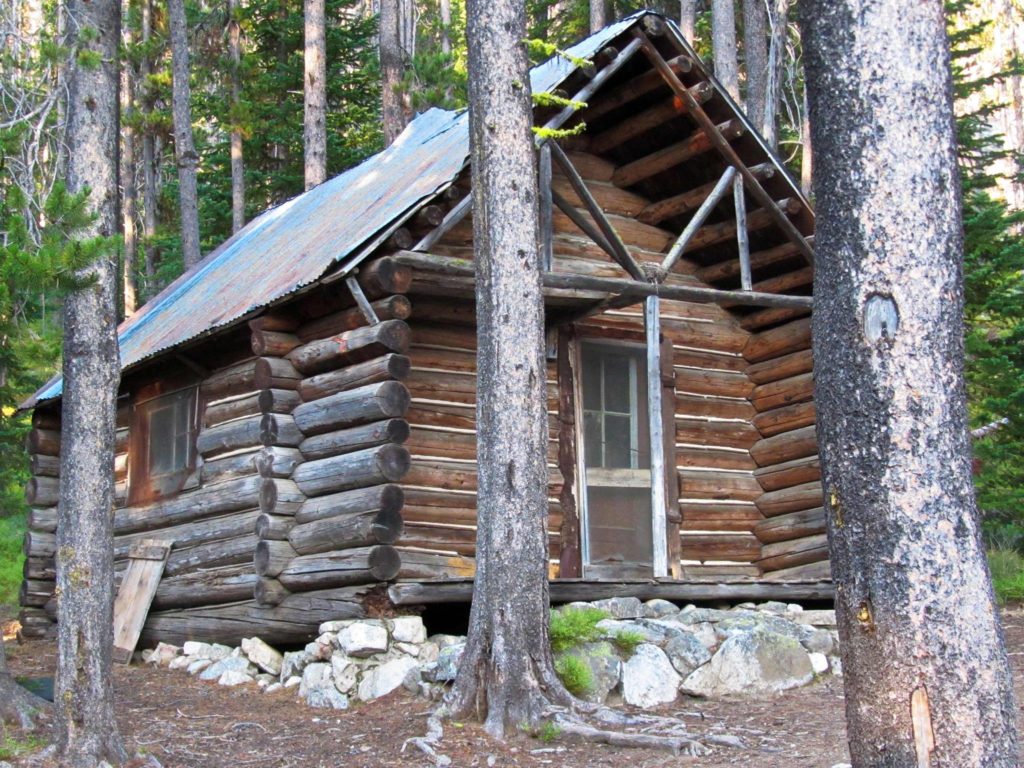

The McCall Base

The McCall Smokejumper program was established in 1943 and led by the godfather of Region 4 smokejumping, Stewart Lloyd Johnson. By 1947, McCall had a permanent base and was home to 50 smokejumpers and their families. “Around this time, the CIA also started recruiting McCall smokejumpers for clandestine operations throughout the world due to their highly specialized training,” explains Todd Haynes, class of 2002 with 472 jumps and counting, and the McCall Smokejumper Base Manager. “For more than 25 years, area smokejumper participated in operations in locations such as Tibet, Vietnam, Laos, and the Arctic Circle.”

Over the years, new partnerships would emerge and major milestones would be achieved in McCall. Like in 1974, an assignment in Alaska kicked off what would become an annual migration of many McCall Smokejumpers to bring support to the Alaskan fire season. Or in 1981, when Deanne Shulman successfully completed rookie training in McCall and became the nation’s first female smokejumper. Or in 2016, when McCall smokejumpers started a historic parachute transition away from the round parachute that had been used since the 1940s in favor of the modern ram-air canopy used by the military and sport parachute jumpers.

“Today,” says Haynes, “the McCall Smokejumper Base is home to 72 smokejumpers, 36 smokejumper spouses, and, perhaps most importantly, 41 kids of smokejumpers who are members of our community.”

The Training

“It was the first day of rookie training in 1998, and I was standing near the ops box waiting for roll call,” recalls Joe Brinkley, class of 1998 with 373 jumps. “Brink” as he is called by his fellow jumpers got his wildland firefighting start in 1991, was hired as a rookie smokejumper in McCall in 1998, and would stay at the base for 24 years, retiring in 2021 as the McCall Base Manager. But before he could do all of that, he had to get through the first day of training.

“At 0800 sharp, the operations foreman belts out ‘when I call your name come out in front of the box and face the crowd,’” he says. Then I hear “Brinkley! And I hustled to the front and turned and faced over 50 veteran jumpers staring back at me – and I swear most of their eyes were red.”

Rookie training is no joke. And the hiring process is tough. “We typically see around 150 wildland firefighters apply each year and only 6 to 8 are selected,” says Brinkley. Applicants must have between five and ten years of wildland firefighting experience before applying for the position and be able to pass a rigorous array of minimum physical requirements.

On the first day, rookies must be able to complete seven pull-ups, 25 push-ups, 45 sit-ups, a one and a half mile run in under 11 minutes, carry a 110-pound pack for three miles in 90 minutes or less, and complete a capacity test by carrying a 45-pound pack for three miles in 45 minutes or less. And that is just the first day of training.

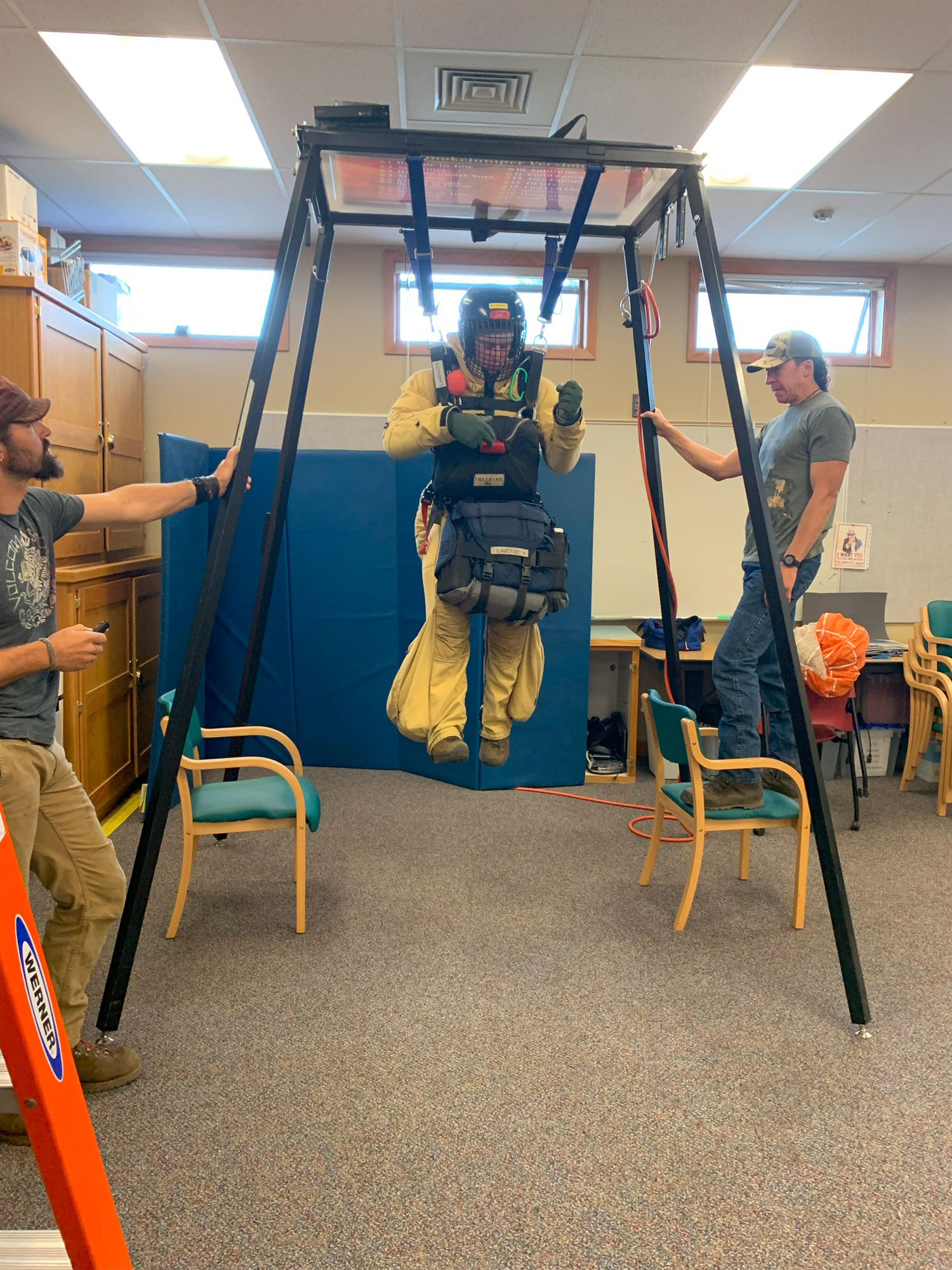

“The intent of rookie training is to push rookies to the absolute limit so trainers can assess how they handle stress in a dynamic environment,” says Brinkley. “It is countless push-us, sit-ups, pull-ups, burpees, dips, and running…always running.” When they aren’t running, rookies, affectionately called “Neds,” practice parachute and cargo retrieval, suit ups, and jump counts while learning equipment nomenclature, wildfire operations, management tactics, and smokejumper history.

Enter week two. “Most consider this the most challenging part of training,” says Brinkley. The focus is on practicing timber letdowns, aircraft exits, parachute landing falls, and parachute malfunction and emergency procedures. “There is lots of running up and down the three-story tower in blistering heat with 70 pounds of jump suit and gear on.”

Then, for the next three weeks, rookies move on to the jump phase. “They will jump twice a day, every day,” Brinkley says. “In high winds, in no wind, into timber and onto ridges. They make mistakes and pay the price with an impromptu run back to the base.” Once they reach jump 25, they complete training and go on “the list,” but they haven’t earned the title of “smokejumper” just yet. They will need to jump a fire to earn that title.

“After 24 years on the smokejumper base and retiring as the base manager,” says Brinkley, “I can tell you that one of the hardest things anyone smokejumper will do, and one of my greatest accomplishments, is to get through rookie training and become a McCall smokejumper.”

The Fire Call

All smokejumpers are on “the list.” This list determines who goes where when a call comes in. To be considered “available,” a jumper must be able to commit to 14 days, the maximum length of an assignment. But as Eric Brundige, class of 1977 with 586 jumps, explains, “it isn’t as easy as just going down the list.”

Frequent requests include a call for a “booster crew,” or reinforcements to a base that needs additional jumpers. “For this type of request, we start at the top of the list and people can accept or pass,” Brundige explains. “But if you get to the bottom of the list and we still need more people, we go back to the top of the list and those jumpers are automatically assigned.”

But why would a jumper turn down an assignment? “There are lots of reasons,” says Brundige. “For example, if a call for a booster crew comes from the Redding base, there may be a bit of hesitation. It is absolutely beautiful country out there,” he laughs, “but most of it is covered in poison oak.” In addition, many requests can transition into new assignments within the 14-day commitment. “Sometimes if you are on a booster crew and an active fire needs additional resources, you can easily find yourself assigned to a hand crew and on a bus to a fire camp with 2,500 people in it.”

The most popular request is the initial attack call. “When that call comes in, the siren goes off and the top eight people on the list get on the airplane and go,” says Brundige. But what is it like to hear that siren sound and know you are headed directly into a fire?

Kyle Esparza, class of 2010 with 284 jumps and counting, says there is always a lot of anticipation. “You never quite know what to expect,” he says. “You could get a call and jump a fire and be back the next night or you could be gone for two weeks in another state.”

At the base when you are on call, Esparza says there is always one ear trained toward the intercom. “You are always listening,” he says. “There is this really faint click you can hear right before the person on the intercom starts talking. It is so faint it is hardly noticeable, but you become trained to hear it.” Sometimes, that click is just a precursor to a routine personnel announcement. But when it isn’t you hear something like “Otter load to the Frank Church” and the buzzer rings out.

Once a fire call comes in, there is a small frenzy of activity. “You get to your gear and when everyone is suited up, you get a high five and a ‘stay safe and have a good jump,” says Esparza. “We really just look like overstuffed teddy bears waddling around in our jump suits,” he laughs. Teddy bears or not, they head out to the jump ship and wait to hear where the fire is going to be.

The Flying

Kacey Rose, class of 1989 with 300 jumps, says there are two types of people when it comes to jumping out of an airplane. The first are the “put me in coach” folks and the second are the “I’d never jump out of a perfectly good airplane” people. “But,” she laughs, “smokejumpers would say ‘there is no such thing as a perfectly good airplane.’” Except perhaps for Jordan Silver.

Silver has been a pilot at the McCall Smokejumper Base for six years and has more than 8,000 hours of flight time, more than half of that in the backcountry. “If anyone knows anything about flying then you know that the Twin Otter is THE airplane,” he says. And the Otter is what is used by the Forest Service for smokejumping. They originated in the 1960s and were built to go low and slow. “They are just the greatest airplane ever,” says Silver. “If I had to pick one airplane to fly for the rest of my career it would be a Twin Otter.”

And a few years ago, Silver had to put the Twin Otter (and his flying skills) to the test. “It was early spring and we got a call for a fire,” he says. So, he started doing his typical routine, what Silver calls “pilot math,” and figuring out how long is it going to take to get there, how much fuel is on board, how much time to get to where they need to go after, how long they can fly, what the current conditions are, and the like. “I was feeling pretty good and did what no one should ever do…I got comfortable,” he says.

It was a wet winter, and an early call. “I am figuring this call will be pretty routine,” Silver says, “maybe a tree or two to put out, quick and easy.” But as they approached the coordinates, a large plumb of smoke appeared. “Enter the ‘Elkhorn Fire’ and the deepest hole you can imagine on the Salmon River and a fire raging,” he says. After circling the area, his spotter identified the necessary jump location and that is when the realization hit. “I am looking at this drainage and I know immediately that this is the most challenging position I have ever been in in an airplane,” Silver says. “Honestly, it scared me.”

But with a job to do, Silver and his team got the jumpers in and the cargo dropped. “The wind was coming down over the top of the mountains and the smoke was incredibly thick, but we worked together to get everything out of the door and after it was over, we settled back after that intense experience to head back to the base for the day,” he says. Which is right about when the radio call came through – they need another load of eight jumpers to this location. “So, we flew home and then turned around to do it all again.”

It was that call, says Silver, that had him asking he question “why am I doing this?” Why not take the cushy airline job in a city with reasonably priced homes? And the answer was actually pretty simple. “Legacy, community, and mission,” says Silver. “The legacy is unrivaled, and as for the community, I get to work with the best people on earth.” Plus, the mission means something. “This is some of the most challenging flying terrain in the lower 48,” he says, “and I get to go out and utilize beautiful airplanes with great people to do something that matters.”

The Jump

“It’s all about the jump!” says Rick Hudson. And he would know. With 35 years and 609 jumps, Hudson has seen just about everything. “A smokejumper’s life is divided between the time before they became aware of jumping and after becoming a smokejumper,” he says. “Once you jump, you look at the world differently.”

Admittedly, some jumps are better than others.

“Picture yourself having finished lunch at My Father’s Place,” says Hudson. “The buzzer at the base goes off announcing the fire call and your heartbeat races, your adrenaline spikes. An hour later you are circling a fire somewhere out over the Salmon River breaks. A dark thunderstorm is just leaving the area and moving up the Main Salmon, but the air is still rough and turbulent. The plane is circling. The spotter is looking for a good jump spot and the plane is circling. As the spotter looks for a possible water source, the plane is circling. As the spotter looks for a place to retrieve the jumpers once the incident is over, yes,” he reiterates, “the plane is circling. You are hot, and sweating and uncomfortable in the confining harness and jumpsuit and you are not the first jumper out of the door. The nausea you are feeling is churning in your stomach as you try to keep your lunch down and focus on the impending jump. But the longer the process is taking the more uncomfortable you feel until eventually you don’t care what is out there. You just want to get out the door and a into the fresh air.”

“Now it’s your turn to jump and you can hear the roar of the aircraft engines, the wind rushing by outside and you listen to the spotter shouting instructions inches from your face. You do your best to comprehend all that information. You nod your head in understanding, but you are actually just concentrating on not throwing up. You wait as the plane banks left for the millionth time. And you wait. You’re clear. The spotter shouts as he checks your static line and you wait, wait for the signal. Then the spotter slaps your shoulder and you part the wind with your helmet as you pitch forward. And you’re falling from the aircraft.”

Hudson paints a vivid picture. He says the sense of descending isn’t that noticeable at first. A bit of a breeze through the face mask and the sense of forward motion, but it isn’t until you get closer to the ground that you really notice the speed. “We are taught in training to look where you want to go, not at the hazards” he says. Hazards like rocks and snags and fallen trees. “Hazards will pull you in like a magnet. Look where you want to go instead.”

“So, you look to the jumpers on the ground holding the drift stream as a wind indicator. You see other jumpers running around and yelling but you can’t hear what they are saying. You line your chute up and prepare for the landing. Oh, get ready. Here comes the ground rush. The last 100 feet of the descent seems to accelerate as you and the earth come together. Sometimes,” Hudson says, “your training and experience just click and you execute a perfect roll and pop up on your feet, a textbook a landing. But most of the time you’re not that quick and coordinated. You smack the ground like a heavy sack of Idaho potatoes and sometimes knock the wind out of yourself.”

“But you have survived another jump. Better get going towards the task you were sent here to do… the fire. You sit up and remove your helmet and realize why the jumpers on the ground were yelling a few minutes ago as a cloud of mosquitoes swarm your face.”

Which is why the number of jumps you make is a badge of honor. “It’s an accomplishment and survival,” says Hudson. And the best part of the job.

The Community

While jumping out of a plane may feel glamours, it doesn’t come without its risks. Eldon Askelson, class of 1966, was both a jumper (with 116 jumps) and a pilot for the McCall base. It was 1966, his first year as a smokejumper. It was a terrible fire year and resources were thin.

He was just coming off his third fire in four days to get restocked when another call came in for a new fire start toward the south fork of the Salmon, just east of Smith Knob. An airplane out of Idaho City had been called in because all other planes from the base were out on other calls. The pilot, Bob Duncan, and spotter, Bobby Montoya came along as part of the package. “It was a Turbo Porter,” recalls Askelson, “and very different than the planes we typically used.” It had a long skinny nose with two porthole windows on the side just next to where the clamshell doors opened.

Because of the plane’s configuration, Askelson and the three other jumpers on board that day had to sit on top of the cargo packs which had shovels and Pulaski handles sticking out the sides. As they approached the jump spot, the jumpers prepared to exit the plane. “The exhaust configuration of the design meant that we had to jump from the left side of the plane and jump out to ensure we cleared the door,” says Askelson.

With the first three jumpers away, it was his turn. He lined up at the door and waited for the signal to go. When he felt the shoulder tap, he jumped…then stopped. “All of a sudden my forward motion stopped and I found myself slamming against the side of the airplane,” he says. “I thought, this is not a good place to be.” He knew he needed to get back to the door. If his parachute opened, it would take down the entire plane.

“I managed to pull myself back up and was just able to reach the bottom edge of the door with one hand,” he says. “Then I dropped my static line as was able to grab the port window with my other hand. Once I got to the door, I realized that my leg strap had been caught on something sticking out from the cargo pack I had been sitting on.” In this precarious position, Askelson says he looked up and saw the spotter, Bobby Montoya in the door with his knife. “I knew from training that in this kind of situation, we are taught to cut the line to save everyone else,” he says. “But I was thinking in my head, ‘Pick me! Pick me.’”

And he saw a quizzical look on Montoya’s face before he disappeared back up to talk to the pilot. During this time, Askelson knew if he had any chance of getting out of this situation he had to get back into the door. So he put all of his effort into getting better purchase on the port window. As he did that, he says he looked up and saw Montoya come back to the door and felt him take hold of his harness. “I saw him yell at the pilot and in an instant, I was back inside the plane, both of us crashing in a tangle in the back of the aircraft,” says Askelson.

“For 56 years, I thought it was our combined effort that got me back into that plane,” he says. Not so. It turns out that there is no chance of pulling someone back inside an airplane by sheer strength alone. Instead, Montoya had worked out a plan for what Askelson now knows was a Zero G Maneuver. “That maneuver made me float outside of the airplane for just enough time for Bobby to pull me back in,” he says. And saved Askelson’s life.

Fast forward to 2007. Garrett Hudson, class of 2007 with 368 jumps and counting (and yes, the son of Rick Hudson), is listening to a tour going through the McCall Smokejumper Base for the umpteenth time. “There is this one part of the video we show that mentions the phrase ‘esprit de corps,’” he says. “I didn’t really know what that meant and never took the time to look it up until recently.” Turns out, “esprit de corps” describes a feeling of pride, fellowship, and a common loyalty shared by members of a particular group.

“And that really sums up what it means to be a smokejumper,” says Hudson. “It is the folks that you work with every day that keep you coming back, ready and excited for the next fire.” It started in 1943 and continues today. It’s the reason rookies fight to make it through training, the reason smokejumpers want to be on “the list,” the reason for the anticipation of the fire call and the helping hands to make sure everyone is suited up and safe. It’s the reason pilots push themselves to get jumpers to challenging locations and why jumpers are willing to brave the heat, nausea, and rush that comes from jumping from a plane to put out a fire. And it is why Elton Askelson is still alive.

If that isn’t mystical, if that isn’t legendary, we don’t know what is.